Inequality in Health Care Online Tutoring

ABSTRACT

Background: Inequality in healthcare is a major concern globally. However, the understanding of the Australian healthcare sector concerning making a difference to the population.

Aim: To assess the inequality in health care in Australia.

Design: A qualitative study design was used.

Method: Systematic review was conducted where studies from 2014 to 2020 were selected based on the determined inclusion criteria.

Results: Residence area, economic status, and demographics (age) are the main factor that affects the delivery of equitable services.

Conclusion: Strategies aimed at providing equitable services should be introduced. A monitoring mechanism should also be ensured for better motoring.

Keywords: Australia, Health Care, Inequality, Systematic Review.

Introduction

It is well recognized that economic and social disadvantages lead to detrimental consequences and risk of mental disorder (Isaacs et al., 2018). World Health Organization (2013) reports and fosters calls through its WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 to direct attention to the disadvantaged group. Caron et al. (2012) show that the increase in income inequality and poverty pose negative psychological distress and mental health. Several studies have argued that the communities at the lower economic level are generally more exposed to health risk factors as well as psychological distress (Isaacs et al., 2018; Godding, 2014).

The scholars examining the health inequalities are instrumental to draw attention to the health of economically and socially vulnerable groups in Australia. These researches have fostered the discussion of the public health action and have encouraged the greater and targeted investment in the healthcare sector, ensuring delivery of the public health services (Hashmi, Alam, & Gow, 2020). Primarily, the research on the health inequalities helps enrich the individuals understanding related to the social disparities in individual’s health, integrating into other markers, such as caste, gender, religion and occupation that leads to compromised health and the quality of life (Meadows, Enticott, & Rosenberg, 2018).

One of the major countries experiencing health inequalities in Australia. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), that although the life expectancy of Australians is of 82 years, as well as the lowest mortality rate, there exists a substantial number of cases related to the age-standardized mortality rates (Godding, 2014). Godding (2014) stated that, in Australia, individuals that reside in rural areas have a mortality rate higher than major cities, i.e., 1.4 times. It also showed that Indigenous Australians had twice the mortality rate as compared to non-Indigenous Australians. A similar situation has continued to prevail for the last 10 years only, however, a comprehensive understanding of it is critical. Previously only Goddin’s (2014) study has investigated the inequality in the healthcare sector of Australia. The time gap, population growth statistics, and the developments in the region have substantially changed from then. Thereby, to bridge this gap, this research intends to study the inequality in the health sector in Australia.

Moreover, given the increasing inequality in the Australian wealth and income, and its continual gradual increase in the long-run given the Gini Index, which has increased to 34% in 2010 from 31% in the 1980s (The World Bank, 2017).

Objectives

The objective of the study are as follows;

- To assess the inequality in health care in Australia.

- To review the researches concerning the health inequalities in healthcare in Australia.

- To discuss the causes and provide a recommendation to overcome inequality in health care in Australia.

Methods

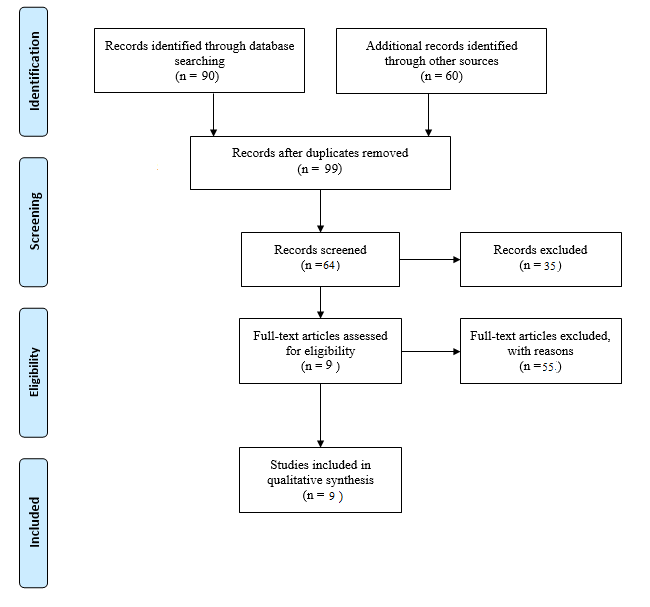

The research has used a qualitative research design for analysis of the inequality in health care in Australia. It used the methods guided by the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). For the systematic review, different researches are gathered ranging from 2014 to 2020 (7 years).

Search Strategy and Data Extraction

The study protocols determined constitute of researching the literature that deals with the health inequalities in the healthcare sector in Australia. For this, researches have determined the search strategy based on different keywords including health inequalities, Australia health sector, health, AND Australia, or inequalities among the Australia health sector. The data was extracted from the different sources include the Scopus, Google Scholar as well as PubMed. Initially, research revealed 250 articles on google scholar, where assessing each database was too extensive for review. This is the reason that certain modifications were made by titles group work, as well as a combination of words.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The first step following the determination of the required criteria based on which the studies would be recruited. The first research led to the inclusion of 150 articles. However, the remaining articles were recruited based on their increasing responsiveness leading to the inclusion of 30 studies. However, based on the analysis and the current situation, only 9 studies were recruited, which meet the determine criteria of research. The inclusion and exclusion criteria require the studies to have or be related to the research objectives determined, following its publishing between the years 2010 to 2020. These must also be published in English. Ways present, where an abstract should also be available for the screening of the study concerning its title, objective and methods (Table 1).

Table 1: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Cohort Study | Blogs |

| Cross-sectional Study | Essays |

| Case-controlled Study with Comparison or Control Group | Websites and Blog |

| Studies reporting the Australian healthcare sector and its inequalities | Older versions of the published studies.

|

| Published from 2014 to 2020 | Published other than 2014 to 2020 |

Results

Concerning the inequalities in healthcare in Australia, the study of Fox & Boyce (2014) can be explored. This study indicates that the mortality rate for the patients is 7 percent higher for the patients that reside in the rural areas, where the inequalities existed for the poor as compared to those that reside in the urban areas. The findings of the research showed that the unchanged environment for the indigenous paper. The literature performed highlighted that the majority of the cancer cases were found in the indigenous individuals from 2001 to 2010. It also showed that the mortality rate was 45 percent high for the indigenous population as compared to the non-Indigenous.

Parker and colleagues (2014) also assessed inequalities concerning the treatment of cancer patients. The findings showed that hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in the Northern Territory is about 5.9 times high for the Indigenous people than in non-Indigenous people. Another study of Currow et al. (2014) on non-small cell lung cancer patients showed that the resection rate was negatively related to the local health district of residence. Such as it found that with lower rates in remote and substantially remote areas, for patients at an older age, having lower SES and absence of private health insurance were all related to the ine1autable treatment of the patients.

Hocking et al. (2014) note that in South Africa, found that the implementation of the centralized cancer treatment model helps in reducing the healthcare inequalities in the sector. Such as it shows that there is no difference in the survival rates of colorectal cancer patients in rural areas and those patients that are living in urban areas.

Australia, racism, health care barriers and intersectionality were examined by Bastos, Harnois, & Paradies (2018). It used the data of the Australian General Social Survey (2014) for the analyses. This was a national representative survey consisted of people whose ages were 15 and above and who lived in 12,932 exclusive houses. It estimated the perspective of intersection and series of multivariable logit regression models. According to the findings, perceived barriers to health care and perceptions of racial discrimination are significantly related. It showed that low-status groups were the major recipient of healthcare service inequality. Findings also show that perceived barriers to health care are predicted by the combination of perceived racism and other forms of discrimination.

The average expenditure of out-of-pocket household on healthcare was analyzed by Callander from 2006 to 2014. It used the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey data for analysis. The findings of the survey showed that the average expenditure of total household on healthcare was linked with the health inequality in the region. This included fees of the practitioners of healthcare, for insurance of private health and medications, was the same after adjustment of inflation. But, according to the 2014 values, there was a rise in them which were from $A3133 to $3199. The lowest-income group possessed a large number of people who had declining healthcare expenditure and there was also a growth in distributing declining healthcare expenditure to the lower-income group with time. If the comparison was made between income decile 1 and income decile 10, so income decile 1 had 15.63 times the odds to have catastrophic health results. According to researchers, society’s poorest people are not protected by Australia’s universal health system because of the financial strains and these are the ones who are inclined to the adverse health conditions.

Hashmi, Alam, & Gow (2020), in Australia, assessed the distributional impact of life shocks (financial hardships and negative life events) on mental health inequality among different socioeconomic groups. This was a longitudinal setting where the Household, Income and Labor Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey data of 13,496 individuals was used for analysis. This data ranges from 2012 to 2017. According to the findings, greater chances of mental illness would be resulted by the exposure to one life shock only in the majority of the underprivileged groups of socioeconomics. Life shocks were also responsible for 24.7% to 40.5% of pro-rich socioeconomic mental health inequality. The results also showed that 21.6% to 35.4% of inequality was contributed by financial hardship shocks and negative life event shocks generated 2.3% to 5.4% inequality when the comparison was made.

Isaacs et al. (2018) reported that social security plays a bigger part, as 60% of people of the lowest income group are dependent upon it for their income. Also, people in the lowest 20% income group consist of aged people of over 65 years, single parents, individuals of the countries of non-English speaking, those who do not live in the capital cities. In such groups, the most common issue is found to be the financial strains, for instance, unemployment or unsecured debt, which can result in increased psychological distress.

Van Eyk et al. (2018) using secondary data analysed the examined psychological-distress health and income relation among the Australians that reside within or outside the capital cities. The findings concluded that the poorest Australians were 1 in 4 who experiences psychological distress at a high level. It indicates the income level as the mental health inequality indicator.

Findings

The findings of the study show that there is a need to prioritize the delivery of efficient healthcare services for the individual that is at an increased risk of health inequality. This would enable the country to deploy efforts that help the influences of absolute poverty and relative disadvantage. Meadows, Enticott, & Rosenberg’s (2018) research discussed that the increasing inequality in healthcare has led to an increase in the deteriorating mental health of the workforce.

Discussion

The analysis of the studies shows that similar to the present study results, various studies have raised international calls for reducing the inequalities in the healthcare sector both globally and nationally (Cloninger et al., 2014; Milanovic, 2016, Picketty, 2014; Jericho, 2017). Increasing access to healthcare and reducing health inequalities are the primary most objectives globally. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008) and Baum et al. (2013) argues that reducing this inequality requires instigation of different strategies that help reduce health inequity and enable better equity access (Freeman et al. 2011). Jolley et al. (2014) stated that dealing with inequality requires funding, policy and organizational support, which are vulnerable to the political and fiscal environment. The findings of the current study also showed that the majority of the psychological therapies have failed to decline the prevalence of mental disorders in Australia. According to it, the national indicators call for the national indicators to reflect on the existing inequalities concerning the population’s mental health as well as formulate groups of those that are at an increasing need for healthcare.

Limitations and conclusion

The study concludes that there requires a need to instigate strategies that help reduce health inequalities in the health care sector. Different monitoring mechanisms should also be introduced for effectively dealing with health policies and programs. The inclusion of the inequalities in the health sector from 2014 to 2020 serves as another limitation. Therefore, future studies should improve the inclusion criteria for drawing findings that could assist in providing equitable services to the underrepresented health areas and populations.

References

Bastos, J. L., Harnois, C. E., & Paradies, Y. C. (2018). Health care barriers, racism, and intersectionality in Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 209-218.

Callander, E. J. (2019). Out-of-pocket health spending in Australia: inequalities identified. PharmacoEconomics & Outcomes News, 824, 21-23.

Caron, J., Fleury, M. J., Perreault, M., Crocker, A., Tremblay, J., Tousignant, M., … & Daniel, M. (2012). Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal South-West. BMC psychiatry, 12(1), 183.

Cloninger, C. R., Salvador-Carulla, L., Kirmayer, L. J., Schwartz, M. A., Appleyard, J., Goodwin, N., … & Rawaf, S. (2014). A time for action on health inequities: foundations of the 2014 Geneva declaration on person-and people-centered integrated health care for all. International journal of person centered medicine, 4(2), 69.

Currow, D. C., You, H., Aranda, S., McCaughan, B. C., Morrell, S., Baker, D. F., … & Roder, D. M. (2014). What factors are predictive of surgical resection and survival from localised non‐small cell lung cancer?. Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8), 475-480.

Fox, P., & Boyce, A. (2014). Cancer health inequality persists in regional and remote Australia. communities, 83, 02_literature_review_models_cancer_services_rural_and_remote_.

Godding, R. (2014). The persistent challenge of inequality in Australia’s health. The Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8), 432.

Hashmi, R., Alam, K., & Gow, J. (2020). Socioeconomic inequalities in mental health in Australia: Explaining life shock exposure. Health Policy, 124(1), 97-105.

Hocking, C., Broadbridge, V. T., Karapetis, C., Beeke, C., Padbury, R., Maddern, G. J., … & Price, T. J. (2014). Equivalence of outcomes for rural and metropolitan patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in South Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8), 462-466.

Isaacs, A. N., Enticott, J., Meadows, G., & Inder, B. (2018). Lower income levels in Australia are strongly associated with elevated psychological distress: Implications for healthcare and other policy areas. Frontiers in psychiatry, 9, 536.

Jericho, G. (2017). Damning evidence of wealth disparity highlights inequality across generations. The Guardian, Australia.

Meadows, G. N., Enticott, J., & Rosenberg, S. (2018). Three charts on: Why rates of mental illness aren’t going down despite higher spending.

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Harvard University Press.

Parker, C., Tong, S. Y. C., Dempsey, K., Condon, J., Sharma, S. K., Chen, J. W. C., … & Davis, J. S. (2014). Hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia’s Northern Territory: high incidence and poor outcome. Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8), 470-474.

Picketty, T. (2014). Translated by Goldhammer A. Capital in the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: The President and fellows of Harvard College.

The World Bank. Gini Index (World Bank estimate). The World Bank (2017). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end= 2010&locations=AU&start=1981&view=chart

Van Eyk, H., Harris, E., Baum, F., Delany-Crowe, T., Lawless, A., & MacDougall, C. (2017). Health in all policies in south Australia—did it promote and enact an equity perspective?. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(11), 1288.

World Health Organization. (2013). Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. Geneva.